Planting and cultivating land for food has been a part of Aotearoa New Zealand’s fabric since its earliest human settlers (Polynesians) between 1200 and 1300 AD, which continued with the arrival of European settlers following Englishman Captain James Cook’s expeditions in the mid to late 1700s. However, before the first European explorers (first Dutchman Abel Tasman, then Cook) came to Aotearoa, Māori already had well-established māra kai (gardening for food) practices to feed themselves.

History shows that ancestors of Māori found that the taro they brought with them from Polynesia did not grow readily, whereas they enjoyed more success with kūmara (sweet potato).

This meant that they had produce they could trade with settlers and were also keen to try growing new plants introduced by the settlers, such as taewa (potato).

“Māori were always ‘gardeners’ in that they grew or managed plants for food. Early colonial contacts introduced new foods, but also the settler lifestyle relied very heavily on self-sufficiency-type lifestyle,” author and Massey University Professor in Ethnobotany, Horticulture and Māori Resource and Environmental Management Nick Rāhiri Roskruge (Ātiawa, Ngāti Tama-ariki) said.

European settlers also had to adapt their crops and practices to what would work in this new environment, and over the years it remained common practice for many New Zealanders to grow their own fruit and vegetables to provide for their families.

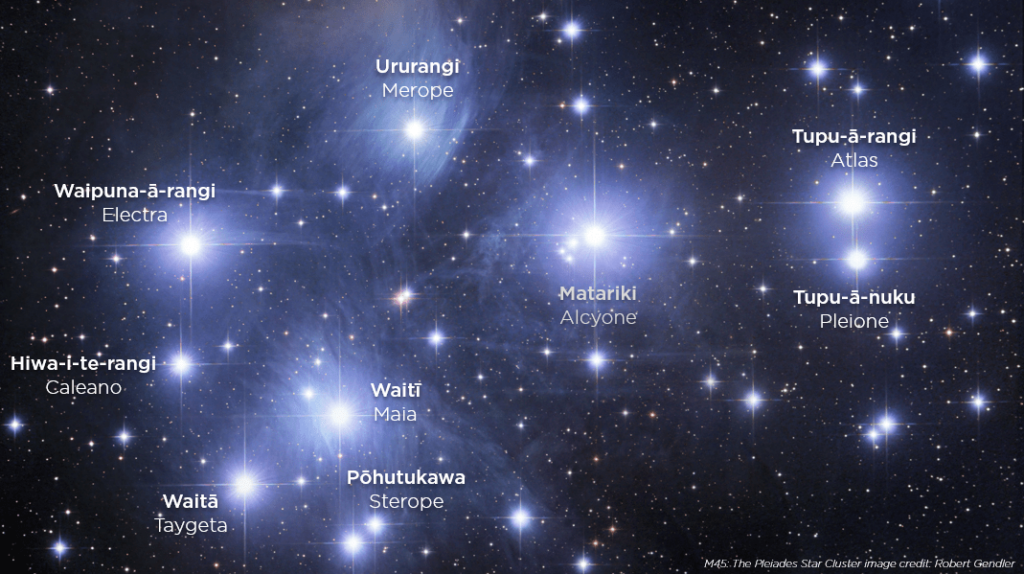

However, one notable difference between Māori farming practices and European farming is that Māori ancestors farmed according to maramataka (the lunar calendar), with Matariki marking the start of a new year.

“Matariki is a celebration of the new year through the recognition of the star constellation as a tohu (to mark) of that period. It recognises the māra kai activity, which should mostly be resting at that time and preparation for the future growing season is being thought out,” he said.

Traditionally, Māori measured time according to the nights rather than the days. Nightly cycles began with the new moon. Each night of a lunar month was named and described according to how favourable or unfavourable it was for fishing, eeling or planting.

For example, key farming dates for kūmara included rākau-nui, the night of the full moon, which was considered a good time to plant, and poutū-te-rangi (February−March), which was considered the best time to harvest. And while different types of food were collected according to the time of year, aruhe (fern root) was a reliable year-round staple.

And while many fishermen still believe they catch more fish on days described as lucky during the fishing maramataka, modern day farming practices in NZ differ vastly from traditional Māori practices.

“Modern farming has little in common with traditional land use – it is animal-centric and based on extensive land use such as pastoralism. Traditional land use was much more localised, seasonal and rotational amongst other things. Māori are now major contributors to the agricultural sector through their uptake of ‘agriculture’ and from small whānau businesses through to incorporations which manage large land bases,” he said.

“I guess the key point here is the role of being kaitiaki or ‘stewards’ over the land resource, which means that practices which look after the resource are the imperative – so Papatuanuku (the representation of the natural world) ahead of people.”

Roskruge, whose professional activities centre around farmer training, food security and crop systems aligned to New Zealand, the South Pacific nations and the Americas, has also written a series of books on māra kai, so that future generations can uphold traditional Māori farming practices.

“Because we need our upcoming generations to know some of what their ancestors knew – to be able to recognise the values of different plants and potential uses or how they relate to other plants. There has been a noticeable gap in this knowledge being available in a modern form. I chair the national Māori Horticultural Collective and one of our aims is to share what we know about our crops or flora and for the benefit of others,” he said.

He recommends his book The Introduction to Establishing a Māra Kai – Ko Mahinga O Toku Māra Kai as a good starting point for those looking to learn more about traditional farming practices.

While you’re here, why not watch some of our On Farm Stories highlighting farming for future generations?

Pania and Eugine King – Gisborne farmers and 2019 winners of the Ahuwhenua Trophy

Richard Scholefield – General Manager at Whangara Farms, an Iwi owned farming operation.