In 2006, I wrote a paper that was published in the journal Primary Industry Management, titled Agriculture’s Greenhouse Gases: how should they be calculated. Eighteen years later I am returning to that topic.

In the intervening years both I and others have been on a learning curve as to the science. But the answers depend not only on the science. This is because greenhouse gas policies also depend on value judgments.

When it comes to value judgments, there is genuine scope for differences of opinion, and no perspective is fundamentally right or wrong.

The important value judgment relating to methane emissions is the time horizon over which comparisons should be made when comparing short-lived and long-lived gases. Methane is the key short-lived gas and carbon dioxide is the key long-lived gas, but with nitrous oxide also important.

Here in New Zealand, we are regularly told that agriculture creates half of the greenhouse gases that the country produces. It is unusual for an important caveat to be added pointing out that this is based on a value judgment of a 100-year time horizon.

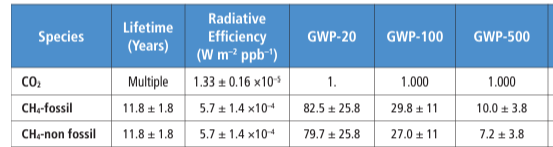

This caveat is important because we would get a totally different answer if we compared methane and carbon dioxide based on their heating effects over 500 years rather than just 100 years. This is because for the relatively short-lived methane, well over 99% of the warming effects are captured within a time horizon of 100 years. However, the currently accepted science in relation to carbon dioxide is that only about one quarter of the warming effects of carbon dioxide emissions occur within this 100-year timeframe.

Hence, if we extend the time horizon to 500 years, then the relative heating effect of a tonne of methane compared to a tonne of carbon dioxide declines to about one quarter of the previous number.

Conversely, if we decrease the time horizon to only 20 years, thereby implying that we are only interested in the environmental effects over the next 20 years and don’t care what happens to the plants, humans and other animals on Planet Earth thereafter, then we would say that the effects of a tonne of methane relative to the effects of a tonne of carbon dioxide increase some three times compared to a 100-year time horizon, and 12 times relative to a 500-year horizon.

The agricultural methane produced in NZ is totally of non-fossil source and hence the appropriate numbers are in the bottom row shown in the table. Those numbers say that the best evidence available to Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change scientists is that if we move from a 100-year horizon to a 500-year time horizon, based on the notion that it is important to have Planet Earth survive for at least that amount of time, then the global warming potential of a tonne of methane drops to the equivalent of 7.2 tonnes of carbon dioxide instead of 27t. This totally changes the global warming importance of methane relative to carbon dioxide. It also greatly reduces the relative significance of agriculture to global warming.

It is important to recognise that the choice of which value to use is not about science but about value judgments. Hence, the choice between these values is not a decision for scientists. It is a decision for society, but society has to be informed.

Among my agricultural friends I often get told methane-emission charges should not be levied because methane is part of the pastoral carbon cycle. The argument is that the methane comes from animals that have eaten carbon-containing plants, and with the plants in turn having obtained their carbon from carbon dioxide. This statement about the carbon cycle is true. But the idea that methane is not an issue because of this cycle is not true.

The IPCC acknowledged about five years ago that the carbon-dioxide equivalent (CO2e) for non-fossil sourced methane should be less than for fossil-sourced methane. That difference is built into the AR6 numbers used in this article. But that does not stop non-fossil methane from contributing to global warming for the time it is in the atmosphere.

I also keep reading arguments from a different group of people that the science of climate change is “settled”. Well, the figures in that table from the AR6 report indicate that, although the IPCC scientists consider the concept of global warming to be settled, they do not regard the specific numbers as settled. The “± numbers’ indicate the level of uncertainty and represent the 95% confidence range based on the ‘known-unknowns’”.

A key point in all of this is that in moving to a 500-year time horizon, I have not diverted in any way from mainstream science. You can argue with me about whether the world we leave behind to future generations is important, but you cannot argue that I have moved from mainstream science in anything I have said above.

Of course, some people believe that Planet Earth time horizons should extend well beyond 500 years. I have no argument with that. However, the relativities of the gases will not change greatly by further increases in the time horizon. A 500-year time horizon is sufficient to emphasise that carbon dioxide is where the biggest action has to lie.

By now, some of my rural readers will be champing at the bit as to why I haven’t been focusing on a different metric for calculating methane’s warming effect, with that metric called GWP*, pronounced “GWP-star”. It is a popular metric among farmers and some agricultural organisations but it is not well understood. Farmers like it because it can give results that they want to hear.

GWP* is also discussed in the latest (AR6) report from the IPCC (p1016). The scientists assess the contribution GWP* could make and in what specific situations it might play a part. They are also explicit that they make no recommendation. And despite what many in the rural community believe, GWP* does not present new science. Rather it is another way of looking at the mainstream science.

Within the IPCC report, there are no figures presented for GWP* as to what the specific value should be. There is a good reason for this. The value depends not only on what an emitter is emitting right now, but also on what they have emitted over the past 20 years.

The formula for calculating GWP* for a particular situation, and here I quote from the AR6 report, is that “the short-lived greenhouse gas emissions are multiplied by GWP100 × 0.28 and added to the net emissions increase or decrease over the previous 20 years multiplied by GWP100 × 4.24”.

What this means is that at a country level if the methane level has been stable over the past 20 years, then the warming value for the current year’s methane can be reduced to just over a quarter of the GWP100 figure.

In contrast, if there was no methane produced 20 years ago, then the GWP* assessment for the current year will be very high.

The formula is what we call a heuristic. It is simply a tool that might or might not be useful in particular situations. It contains no inherent science beyond what is embedded in the GWP100 measure, but it does give credit for historical emissions.

In other words, a high historical-emitter such as NZ can sail along with a low assessment, and continue to do what it has been doing. In contrast, a country like India that has been increasing its livestock production would face a very high assessment per unit of current emissions.

The problem with this is that the atmosphere does not distinguish between emissions sourced from NZ or India. A tonne of added methane warms the atmosphere by a specific amount regardless of which country it comes from.

Another way of putting it is that a country like NZ would be “grandfathered” and to a large extent would not be pressured to make change. We would actually be rewarded for our historical emissions. This idea is totally against the Paris 2015 agreement, which aims to assist rather than penalise developing countries.

So far, most of the promotion for GWP* has been occurring in an echo chamber. The agricultural proponents did get together at the recent COP28 in Dubai among the more than 99,000 attendees, but it was not picked up as far as I can ascertain by any international media.

There has also been a developing literature criticising the GWP* metric on both ethical and practical grounds. I have seen none of that in the NZ media, but it is powerful.

The new coalition government has committed to a 2024 review of methane metrics and that is going to be very interesting. I am not convinced that either NZ’s farmer organisations or the government are currently on top of the issues.

There is a lot more to be said about methane and warming. Accordingly, I plan a follow-up to this article in two weeks.