Marine farming is booming in New Zealand, with mussels, oysters and salmon riding the ‘blue economy’ wave.

Earlier this month Oceans and Fisheries Minister David Parker said seafood exports are expected to hit $1.9 billion in the year to June 30, 2022, a 9% increase on the previous year.

“We’re seeing good progress in the export recovery of our seafood sector … This most recent forecast should give the seafood sector reason to be optimistic as it continues to provide high-quality products into international markets where there is tight supply,” Parker said.

NZ also has a wealth of diversity of seaweeds growing along its coastlines – more than 900 species – making it one of the world’s marine biodiversity hotspots and a market just waiting to be tapped into.

But how could this bountiful natural resource be farmed for commercial gains?

Despite the variety and abundance of NZ seaweed, the industry is generally under-developed in regard to its commercial potential. Right now it is described as “fledgling but highly dynamic seaweed sector operating at small-scales”, but many gaps and barriers exist, limiting the potential growth. But there is an opportunity to produce and sell seaweed products that are different from those from other parts of the world.

Cawthron aquaculture group manager Serean Adams, who is the project leader for a $560, 000 (originally $500, 000) two-year Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge project on developing a seaweed sector framework in NZ, says while NZ’s seaweed sector is in its infancy there is significant interest in seaweed here, with the establishment of a commercial seaweed industry under active exploration by government, industry and iwi.

“Seaweed farming in the right location and at the right scale can have positive benefits on the environment, as well as supporting carbon sequestration and climate regulation,” she said.

“It can (also) be used to replace products that are produced unsustainably.

“There are pockets of product innovation happening at small-scale (particularly in biostimulants, but also foods and supplements), but growth is constrained by regulation and an underdeveloped local seaweed supply chain.

“It (also) fits well from the perspective of regional job creation and as industry with a small environmental footprint, it could help displace products that are less sustainable – replace products with higher greenhouse gas footprints.”

Current knowledge of domestic seaweed species is mostly focused on their ecology; information on fundamental biology and cultivation of species is sparse and scattered, making it difficult to access. Seaweed farmers should also incorporate Māori kaitiaki to ensure the environmental and social benefits of seaweed farming are realised.

Adams and her team are focused on markets and regulation, including future market opportunities and priorities; exploring which species have characteristics of commercial interest and Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi considerations; and the environmental effects of regenerative seaweed aquaculture (both positive and negative, ecosystem services and bioremediation).

The team is also co-developing a seaweed sector framework for NZ and are testing the framework using seaweed case studies to understand how it can effectively operate across different scales – local, regional, national and small to large businesses.

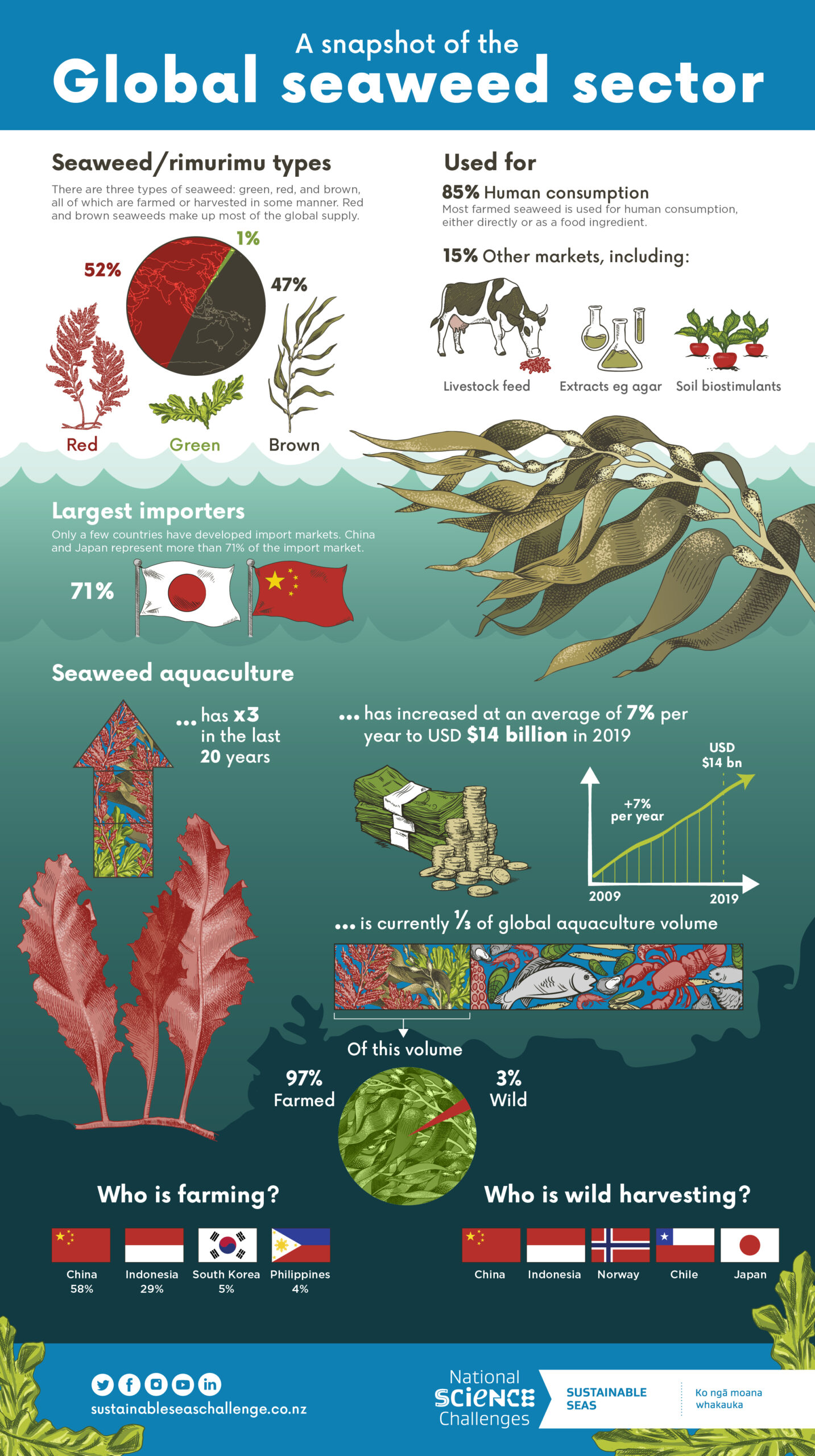

Most farmed seaweed is used for human consumption, either directly or as a food ingredient (85%); the balance is used for a range of markets, including livestock feed supplements, extracts (e.g. agar) and other uses like soil biostimulants.

“Asparagopsis species are the key species being targeted for methane inhibition but other species may also have some effect on methane inhibition as many seaweeds contain bromoform and other halogenated methane analogues, which are the bioactive substances inhibiting methane production when fed to livestock. This is something many scientists throughout the world are currently working on – how to grow Asparagopsis at scale for livestock feed supplement,” she said.

Seaweeds also have a role in carbon sequestration and climate regulation.

“Although much of the carbon sequestered by seaweeds that are farmed is likely to be released back into the atmosphere once it is harvested and used in products (e.g. foods), some will be permanently sequestered,” she said.

“From wild beds, this amount is estimated to be about 1% locally sequestered and about 9% sequestered to the deep sea. The amount from farmed seaweeds has not been estimated. It may be less because the seaweed is harvested before large amounts slough off or it could be argued that it may be higher since seaweed farms are more likely to be located over soft sediment and the potential for it to be sequestered in sediment is greater than wild, rocky kelp forests.”

Most marine farms are located in sheltered bays and near coastlines, but coastal access is not necessarily required in the immediate vicinity. Temperature, however, plays an important role.

“We are working on developing systems for more exposed conditions,” she said.

“Certain species may favour sheltered conditions over more exposed ones and vice versa. Similarly the temperature range that a particular species grows at is an important consideration, particularly in a changing environment. For example, bladder kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) does not grow well when water temperatures exceed 18degC for extended periods.”

Processing harvested seaweed depends on the end product requirements.

“For some products (e.g. biostimulants) only basic processing is required but other products may require more complex processing and certification (e.g. health supplements),” she said. “Companies may decide to be vertically integrated (from hatchery through to retail), whereas others may choose to participate only in certain parts of the value chain.”

Within seaweed food products, China and Japan are the largest importers representing more than 71% of the global market.

While the Government’s Aquaculture Strategy includes investment and research projects to support industry growth in an effort to potentially turn aquaculture into a $3b industry by 2035, a clear pathway for ecosystem services markets from seaweed needs to be developed and managed, along with a fit-for-purpose cross-agency regulatory framework including international harmonisation, marine spatial planning, consenting, permitting and standards setting requirements, to ensure commercial viability within NZ’s ‘blue economy’.

Last year the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) invested $2 million in a pilot seaweed farming project through its Sustainable Food and Fibre Futures fund (SFF Futures), which “aims to help seaweed farmers throughout New Zealand to establish their own farms, using a regenerative ocean farming model”.

The research team is set to publish the final Seaweed Sector Framework for NZ in September.

You can learn more about Cawthron’s other projects below.